Prologue

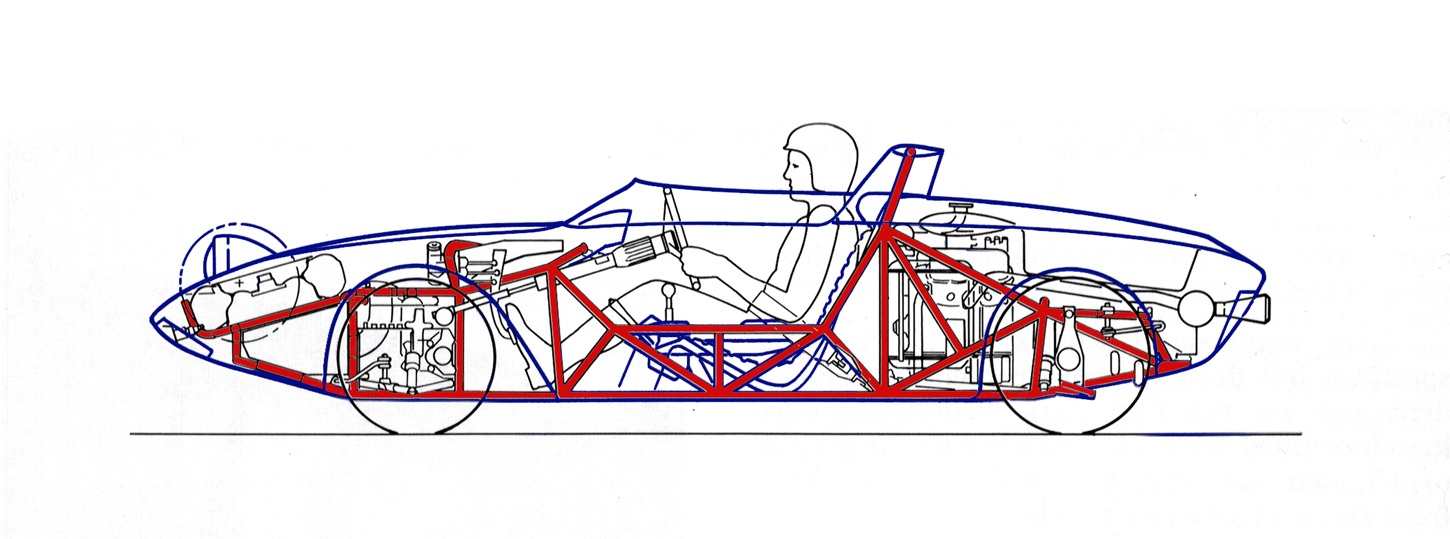

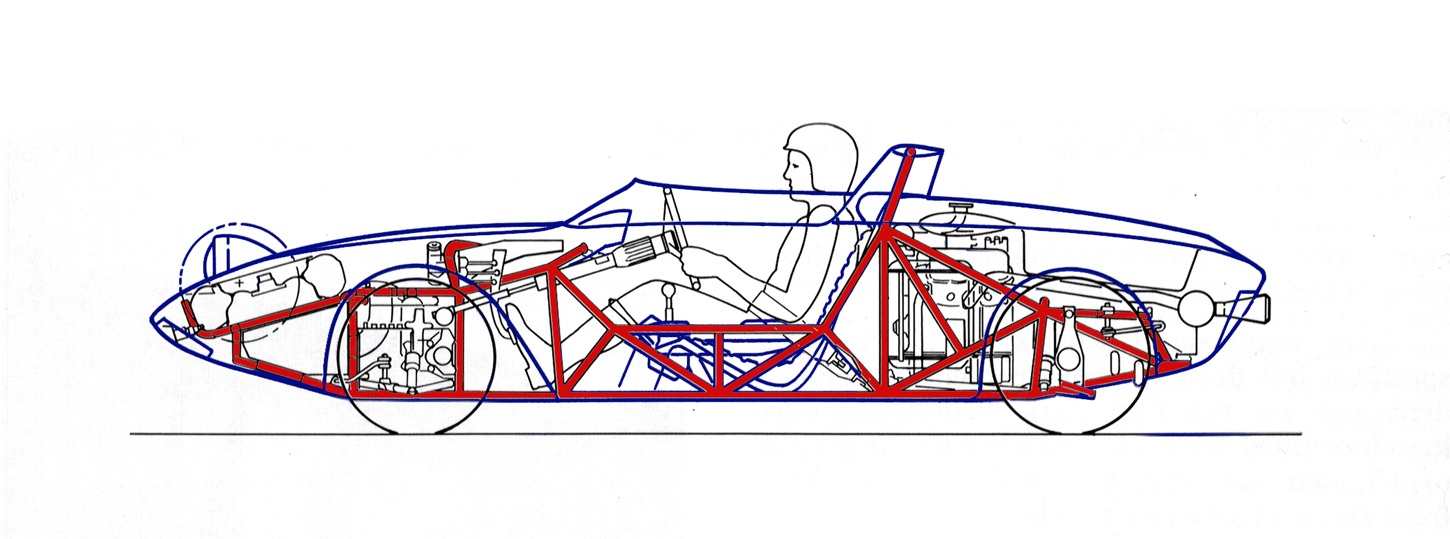

It was a warm October afternoon in up-state New York. The site of the 1962 United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. For the traditional ceremony to declare the track clear for competition, honorary track Marshall Stirling Moss made a couple of quick laps in a white Ford roadster. This was no hotted up Falcon. This was a mid-engine sports car, with an air-foil roll bar that stood only forty inches high. In every way the car, dubbed Mustang One, foreshadowed not the car that was to take its name to market, but an international racing effort that was soon to take shape under the banner of Ford’s Total Performance program. One of the most ambitious promotional programs ever undertaken by an automotive manufacturer, Total Performance saw a number of the company’s divisions working independently, often at cross purposes, to fashion a new image for the Blue Oval.

What the Mustang One symbolized was that Ford was entering uncharted territory. It would be the first American motor company to seriously enter the European defined and dominated World Sportscar Manufacturers Championship. To undertake this action Ford found itself in the most unlikely position of Starting from Scratch.

When the father of the Falcon, Robert Strange McNamara, was invited to join JFK’s administration in January 1960 it signaled a change within Ford. The Falcon had been Ford’s first foray into the brave new world of compact cars. Its rather staid appearance reflected not only McNamara’s automotive vision, but that of the late fifties’ buying public; compact cars were economical transportation. Period. The Falcon’s sales numbers of 400 thousand annually had certainly validated McNamara’s interpretation of a compact economy car.

McNamara’s young replacement saw things differently. The thirty-six year old Lee Iacocca noticed the accessories being bought for the Falcons. These showroom add-ons implied that the compact was being seen as something more than mere brownbag transport. Interior trim upgrades and performance options showed the Falcon buyer was reinterpreting Ford’s economy car as a small sporty car. A broader social implication lay within these purchasing statistics; there was a sea change about to envelop the American automobile industry. What Iacocca saw was a large, well educated generation in America’s demographic future. The very definition of the car buyer.

There was one small problem for Ford in this promise of a greatly expanding youth market, Dearborn’s image, or lack of one. The Blue Oval was firmly attached to the Country Squire and the functional economy of the Falcon in the public mind. Products targeted at an aging parental demographic would hardly inspire this new performance minded market to stampede into Ford showrooms.