The morning of the first day of practice John Surtees took out his new four-liter 330-P Ferrari and set a new lap record at three minutes and forty-five seconds for the 8.3 mile circuit; recording 193.8 on the Mulsanne straight. It was Spring in the farm country of France, and by mid-morning it was raining steadily. With a slick track Ford of France driver Joe Schlesser, took to the track, in one of the first two Ford GTs completed. Because of the promotional departments insistence that the car appear in New York, Lunn’s team hadn’t had any time to perform even the preliminary shake down tests. So this would be a very public rain-soaked trial by fire, on what was reported to be dry weather tires. . Near the end of the Hunaudiere straight there is a slight right hand bend. It runs through a grove of pine. One goes through it at near terminal velocity. While exploring what exactly terminal velocity was Schlesser's car went light. With steering and braking ineffective, he went straight on into the very damp and unmoved pines. His deceleration was immediate. Schlesser, for his part, crawled from the now totaled prototype. Back at the pits he got in a Cobra to shake it all off, and set a respectable GT class lap time. In quick succession Roy Salvadori, in the second team car, got mildly airborne at the Mulsanne hairpin and was unceremoniously planted in the sandbank. Completely fracturing the bonded plastic hood. Test over.

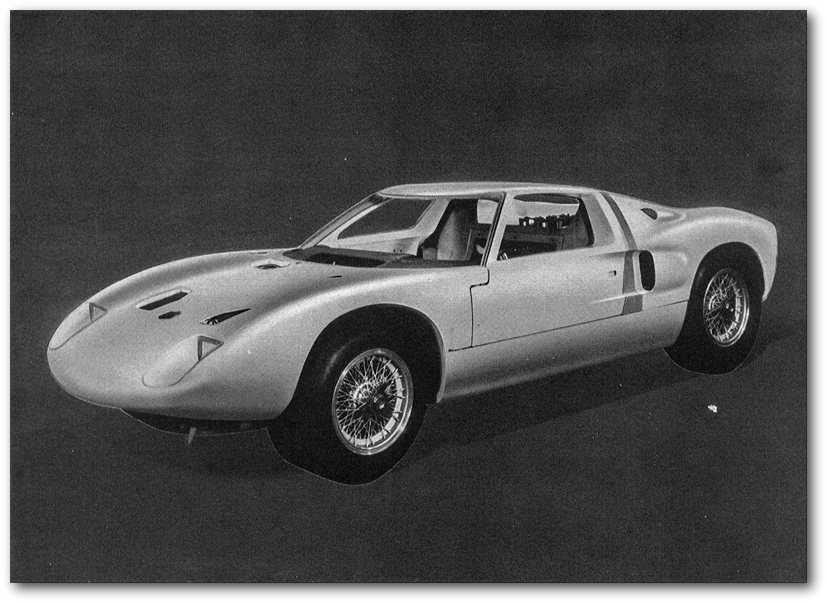

Aerodynamics looked to be the biggest problem. One of the most significant elements of the GT40, and its precursor the Mustang I, was its pioneering flat-plane aerodynamic thesis. Roy Lunn's engineering and John Najjar & Jim Sipple's design had chosen an original and innovative aerodynamic design direction. This at a time when only the ingenious Carlo Chiti and Richie Ginther, with their trim-tab concept, had radically transformed the rounded traditions of pre-war French aero design which were still very prevalent in 1961. So much so that no one in the racing community then had caught on to what Chiti and Ginther had done at Ferrari. So Lunn, Najjar and Sipple were breaking ground with an entirely different aero thesis. The early tests at the Maryland University wind tunnel had shown a considerable lift at the projected 200 mile an hour speeds. To adjust for this the nose was progressively lowered. But with the first car in New York for promotion, and the second car completed just before transshipment to LeMans, no real world tests could be done. Or modifications made for that matter. This was all to be expected as these were the first of their kind, ultra high-speed coupes. So with every test run they were navigating uncharted aerodynamic territory. Unfortunately for the team from Slough this preliminary testing was being done in the glare of full court press. Ford’s PR department had realized early on the value this effort would have for its European operations, and they were working overtime. So was the team in Slough, but its easier to produce ink than a fully sorted sports racing prototype that will last 24 hours.

The June newspapers had told little next to the ball scores about LeMans. So, it was left until the September ’64 magazines that any detail could be attributed to Ferrari’s victory at LeMans, or the first competition at the Nürburgring for the Lola Fords, as they were still incorrectly referred to.

By the running of the Nürburgring the aerodynamic package had been further evolved by reshaping the rear deck surface to incorporate those aero trim tabs of Chiti and Ginther. This resulted in that pushrod Indy engine getting its substantial power to the ground. So much so that Phil Hill’s burn-out at the start nearly collected a course Marshall. A more realistic appraisal of the car’s performance was its second place qualifying time of 9 minutes, four seconds and change on this 14 mile circuit of the most challenging character. This was one of the great years for John Surtees and Ferrari. Surtees qualifying time was a blistering 8 minutes 57 seconds, almost on par with his Formula One times on this German circuit.

The GT40 was no car you could run across the track to for a LeMans type start, jump into an open cockpit, light it off and nail it. The entire field roared around Phil Hill as he negotiated getting in the coupe, belted up and lit up the tires. Phil got on pace quickly though, moving into second place. With the compliment of new aerodynamic devises mounted since the LeMans trials, the car was indeed getting grip. And now that it was firmly attached to the ground, this 1000 klm run through the Eiffel mountains, with its 145 corners to the lap, was about to give all the attached bits a good shake down.

Surtees was showing that his qualifying lap was no fluke as he pulled away from Hill and the Ferraris of Scarfiotti and Graham Hill. After a couple of laps watching Hill’s pace the two Ferraris pulled by into second and third. Pitting from fourth on the eleventh lap of 44, Hill turned over to Bruce McLaren. McLaren made no impression on the Ferraris of Scarfiotti and Hill, as they could make no ground on Surtees. Lap fifteen saw McLaren in the Ford pits, hood up, with the crew examining the rear suspension mounts that had now come adrift the chassis. Though the Ford effort had ended in the pits, and the PR department had nothing here, Lunn and the team from Slough were showing rapid progress. And all of Europe respectfully, if a bit begrudgingly, echoed with the acceptance that Ford was a real threat and the only team capable of running with Ferrari, if not yet to the finish.

Front suspension

Rear suspension

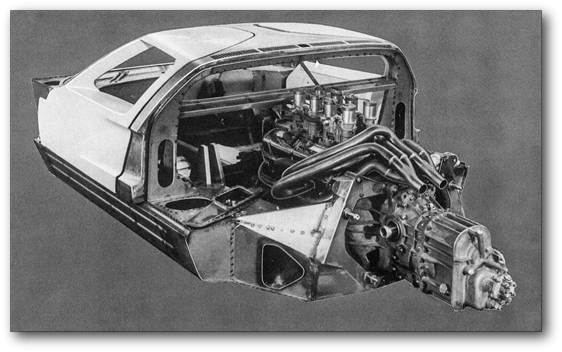

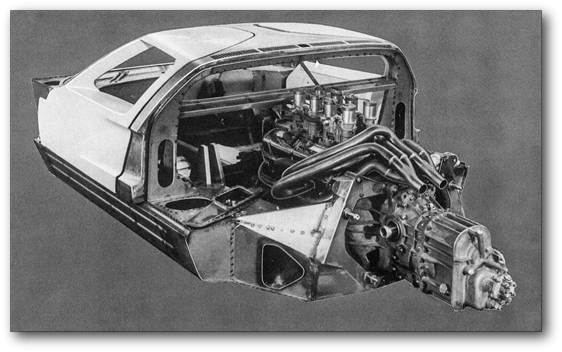

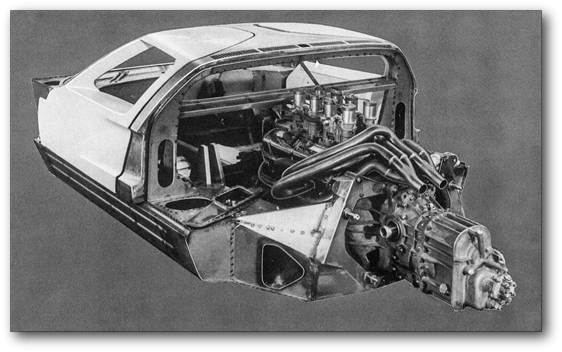

Here the engine is mounted with its real set of headers.

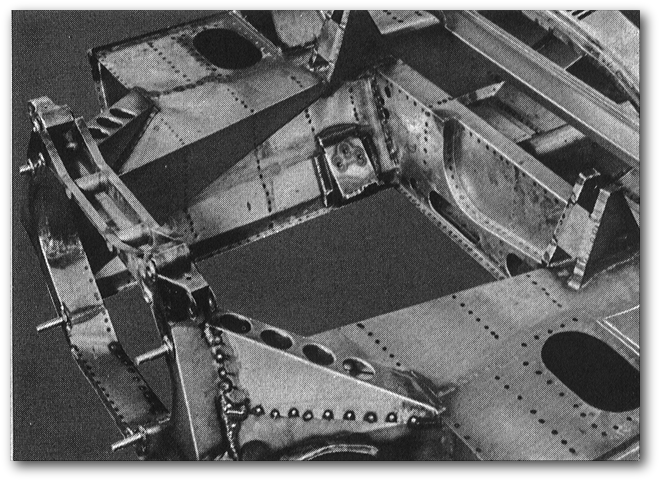

Steel Monocoque, here showing the engine bay.

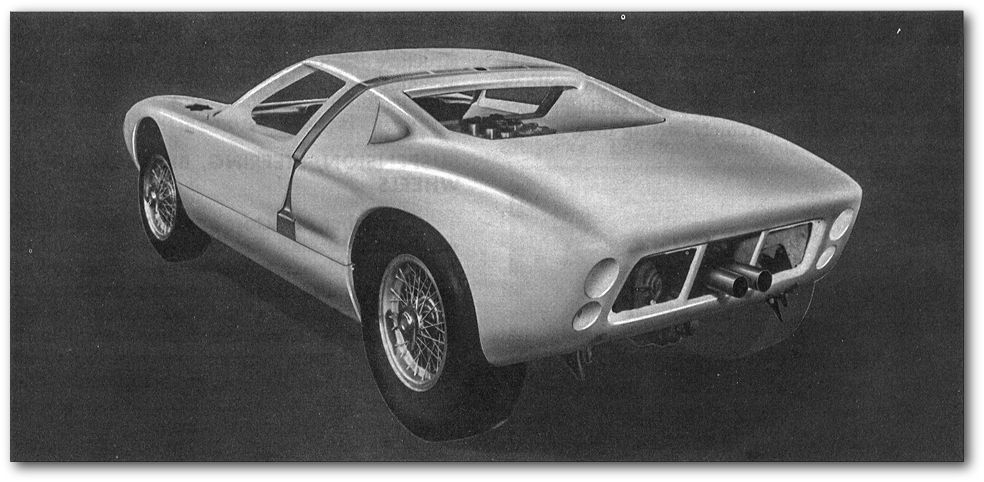

Early panel fit.