and weight - a step that relegated the leviathan racers to history with one stroke. The new specification of 4.5 liters played quite well into the hands of the French, particularly Lyon-Peugeot, the Parisian racing arm of the motor company. Only a few years earlier that small group of engineers and drivers, derisively known as les Charlatans, had developed the first twin-cam engines, and with smaller displacement, swept all before them aside - including the entire field at Indianapolis, trounced by Jules Goux in 1913.

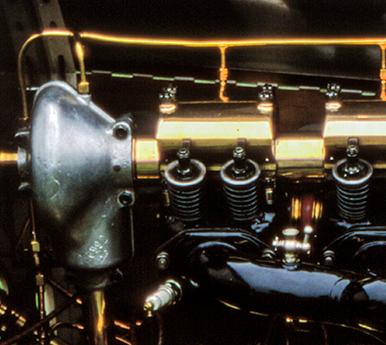

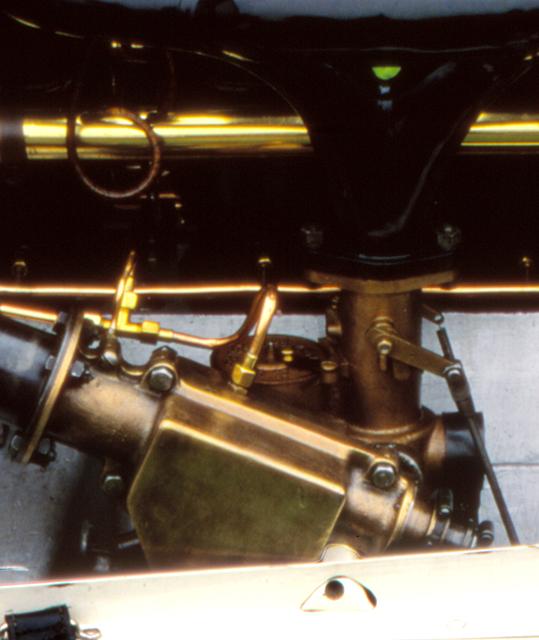

Paul Daimler and the management at Mercedes were well aware of the challenge presented by their return to Grand Prix competition at this significant race, and they responded as Mercedes always would: to compete would mean to succeed. Engineering advances had been rapid since '08 inside Stuttgart; the company had entered the aviation business, and the new car profited by its technologies. For lightness and strength the engines were constructed around four steel cylinders with painstakingly welded steel water jackets. For efficiency the cam - which had always resided in the crankcase - was lifted above the inclined valves, of which there were four per cylinder. For performance, four spark plugs ignited the mixture in

Paul Daimler and the management at Mercedes were well aware of the challenge presented by their return to Grand Prix competition at this significant race, and they responded as Mercedes always would: to compete would mean to succeed. Engineering advances had been rapid since '08 inside Stuttgart; the company had entered the aviation business, and the new car profited by its technologies. For lightness and strength the engines were constructed around four steel cylinders with painstakingly welded steel water jackets. For efficiency the cam - which had always resided in the crankcase - was lifted above the inclined valves, of which there were four per cylinder. For performance, four spark plugs ignited the mixture in

VGM

VELOCITY GROUP MAGAZINE

Twilight of Epoque

The team had occupied the small hotel

just outside Lyon for three months, testing

without letup. The team drivers - Pilette,

Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer

- and the Mercedes team riding mechanics

had spent eight hours a day covering every

inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the

time it was discussed, endlessly. Much

later, automotive historians would estimate

that Mercedes employees had driven,

ridden or walked 30,000 miles in

preparation for this race; but the

discussions at table, filled with fine

Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had

contributed most to the development of the

car.

For all concerned, more was at stake

than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After

Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the

French had lost interest in Grands Prix,

and the expense of organizing them. The

return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an

absence of six long years put the French

and Germans head-to-head at a time when

those two nations contended for world

leadership in automotive design. The rules

set forth by the French Auto Club for the

first time addressed total displacement,

rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore

each cylinder. (By insisting on sixteen valves and sixteen plugs, Mercedes created one of the most maintenance-intensive four-cylinder engines in history, and didn't care a bit, as usual.)

The most visible influence of aero-engineering was the aluminum-skinned body, with its low, tapering cowl and its V-shaped radiator set behind the front axle. The car manifested a nearly visible tension and must have been a revelation to spectators who still measured a Formula car by the imposing bulk of the top-heavy 10 and 12 liter racers…something like the effect, forty years later, of a 300SL Gullwing on a car-watcher whose benchmark was a 1955 Detroit sedan. Yet, in a car of meticulous engineering and superb finish, why were there no front brakes? True, they had been included in the competition's cars; equally true, other respected constructors including Bugatti still spurned them. For us, with the luxury of hindsight, it is hard to justify the omission on a car with large wire wheels mounted well clear of the body; large, well-designed drums would have been aggressively cooled and notably effective. But history is history, development time was not at hand, and Mercedes was head-to-head with cars that could corner more

The most visible influence of aero-engineering was the aluminum-skinned body, with its low, tapering cowl and its V-shaped radiator set behind the front axle. The car manifested a nearly visible tension and must have been a revelation to spectators who still measured a Formula car by the imposing bulk of the top-heavy 10 and 12 liter racers…something like the effect, forty years later, of a 300SL Gullwing on a car-watcher whose benchmark was a 1955 Detroit sedan. Yet, in a car of meticulous engineering and superb finish, why were there no front brakes? True, they had been included in the competition's cars; equally true, other respected constructors including Bugatti still spurned them. For us, with the luxury of hindsight, it is hard to justify the omission on a car with large wire wheels mounted well clear of the body; large, well-designed drums would have been aggressively cooled and notably effective. But history is history, development time was not at hand, and Mercedes was head-to-head with cars that could corner more

Twilight of Epoque

The team had occupied the small hotel

just outside Lyon for three months, testing

without letup. The team drivers - Pilette,

Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer

- and the Mercedes team riding mechanics

had spent eight hours a day covering every

inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the

time it was discussed, endlessly. Much

later, automotive historians would estimate

that Mercedes employees had driven,

ridden or walked 30,000 miles in

preparation for this race; but the

discussions at table, filled with fine

Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had

contributed most to the development of the

car.

For all concerned, more was at stake

than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After

Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the

French had lost interest in Grands Prix,

and the expense of organizing them. The

return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an

absence of six long years put the French

and Germans head-to-head at a time when

those two nations contended for world

leadership in automotive design. The rules

set forth by the French Auto Club for the

first time addressed total displacement,

rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore

The team had occupied the small hotel just

outside Lyon for three months, testing

without letup. The team drivers - Pilette,

Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer

- and the Mercedes team riding mechanics

had spent eight hours a day covering every

inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the

time it was discussed, endlessly. Much

later, automotive historians would estimate

that Mercedes employees had driven,

ridden or walked 30,000 miles in

preparation for this race; but the

discussions at table, filled with fine

Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had

contributed most to the development of the

car.

For all concerned, more was at stake

than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After

Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the

French had lost interest in Grands Prix,

and the expense of organizing them. The

return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an

absence of six long years put the French

and Germans head-to-head at a time when

those two nations contended for world

leadership in automotive design. The rules

set forth by the French Auto Club for the

first time addressed total displacement,

rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore

and weight - a step that relegated the leviathan racers to history with one stroke. The new specification of 4.5 liters played quite well into the hands of the French, particularly Lyon-Peugeot, the Parisian racing arm of the motor company. Only a few years earlier that small group of engineers and drivers, derisively known as les Charlatans, had developed the first twin-cam engines, and with smaller displacement, swept all before them aside - including the entire field at Indianapolis, trounced by Jules Goux in 1913.

Paul Daimler and the management at Mercedes were well aware of the challenge presented by their return to Grand Prix competition at this significant race, and they responded as Mercedes always would: to compete would mean to succeed. Engineering advances had been rapid since '08 inside Stuttgart; the company had entered the aviation business, and the new car profited by its technologies. For lightness and strength the engines were constructed around four steel cylinders with painstakingly welded steel water jackets. For efficiency the cam - which had always resided in the crankcase - was lifted above the inclined valves, of which there were four per cylinder. For performance, four spark plugs ignited the mixture in

The team had occupied the small hotel just outside Lyon for three months, testing without letup. The team drivers - Pilette, Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer - and the Mercedes team riding mechanics had spent eight hours a day covering every inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the time it was discussed, endlessly. Much later, automotive historians would estimate that Mercedes employees had driven, ridden or walked 30,000 miles in preparation for this race; but the discussions at table, filled with fine Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had contributed most to the development of the car.

For all concerned, more was at stake than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the French had lost interest in Grands Prix, and the expense of organizing them. The return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an absence of six long years put the French and Germans head-to-head at a time when those two nations contended for world leadership in automotive design. The rules set forth by the French Auto Club for the first time addressed total displacement, rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore

Paul Daimler and the management at Mercedes were well aware of the challenge presented by their return to Grand Prix competition at this significant race, and they responded as Mercedes always would: to compete would mean to succeed. Engineering advances had been rapid since '08 inside Stuttgart; the company had entered the aviation business, and the new car profited by its technologies. For lightness and strength the engines were constructed around four steel cylinders with painstakingly welded steel water jackets. For efficiency the cam - which had always resided in the crankcase - was lifted above the inclined valves, of which there were four per cylinder. For performance, four spark plugs ignited the mixture in

The team had occupied the small hotel just outside Lyon for three months, testing without letup. The team drivers - Pilette, Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer - and the Mercedes team riding mechanics had spent eight hours a day covering every inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the time it was discussed, endlessly. Much later, automotive historians would estimate that Mercedes employees had driven, ridden or walked 30,000 miles in preparation for this race; but the discussions at table, filled with fine Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had contributed most to the development of the car.

For all concerned, more was at stake than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the French had lost interest in Grands Prix, and the expense of organizing them. The return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an absence of six long years put the French and Germans head-to-head at a time when those two nations contended for world leadership in automotive design. The rules set forth by the French Auto Club for the first time addressed total displacement, rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore

each cylinder. (By insisting on sixteen valves and sixteen plugs, Mercedes created one of the most maintenance-intensive four-cylinder engines in history, and didn't care a bit, as usual.)

The most visible influence of aero-engineering was the aluminum-skinned body, with its low, tapering cowl and its V-shaped radiator set behind the front axle. The car manifested a nearly visible tension and must have been a revelation to spectators who still measured a Formula car by the imposing bulk of the top-heavy 10 and 12 liter racers…something like the effect, forty years later, of a 300SL Gullwing on a car-watcher whose benchmark was a 1955 Detroit sedan. Yet, in a car of meticulous engineering and superb finish, why were there no front brakes? True, they had been included in the competition's cars; equally true, other respected constructors including Bugatti still spurned them. For us, with the luxury of hindsight, it is hard to justify the omission on a car with large wire wheels mounted well clear of the body; large, well-designed drums would have been aggressively cooled and notably effective. But history is history, development time was not at hand, and Mercedes was head-to-head with cars that could corner more

The team had occupied the small hotel just outside Lyon for three months, testing without letup. The team drivers - Pilette, Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer - and the Mercedes team riding mechanics had spent eight hours a day covering every inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the time it was discussed, endlessly. Much later, automotive historians would estimate that Mercedes employees had driven, ridden or walked 30,000 miles in preparation for this race; but the discussions at table, filled with fine Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had contributed most to the development of the car.

For all concerned, more was at stake than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the French had lost interest in Grands Prix, and the expense of organizing them. The return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an absence of six long years put the French and Germans head-to-head at a time when those two nations contended for world leadership in automotive design. The rules set forth by the French Auto Club for the first time addressed total displacement, rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore

The most visible influence of aero-engineering was the aluminum-skinned body, with its low, tapering cowl and its V-shaped radiator set behind the front axle. The car manifested a nearly visible tension and must have been a revelation to spectators who still measured a Formula car by the imposing bulk of the top-heavy 10 and 12 liter racers…something like the effect, forty years later, of a 300SL Gullwing on a car-watcher whose benchmark was a 1955 Detroit sedan. Yet, in a car of meticulous engineering and superb finish, why were there no front brakes? True, they had been included in the competition's cars; equally true, other respected constructors including Bugatti still spurned them. For us, with the luxury of hindsight, it is hard to justify the omission on a car with large wire wheels mounted well clear of the body; large, well-designed drums would have been aggressively cooled and notably effective. But history is history, development time was not at hand, and Mercedes was head-to-head with cars that could corner more

The team had occupied the small hotel just outside Lyon for three months, testing without letup. The team drivers - Pilette, Lautenschlager, Wagner, Sailer and Salzer - and the Mercedes team riding mechanics had spent eight hours a day covering every inch of the 23.5 mile course; the rest of the time it was discussed, endlessly. Much later, automotive historians would estimate that Mercedes employees had driven, ridden or walked 30,000 miles in preparation for this race; but the discussions at table, filled with fine Lyonnais food and Rhône wine, had contributed most to the development of the car.

For all concerned, more was at stake than a beautiful Lyonnais summer. After Mercedes' victory in '08 at Dieppe the French had lost interest in Grands Prix, and the expense of organizing them. The return of Stüttgart to Grand Prix after an absence of six long years put the French and Germans head-to-head at a time when those two nations contended for world leadership in automotive design. The rules set forth by the French Auto Club for the first time addressed total displacement, rather than the vagaries of cylinder bore